The milpa is a common agricultural technique in Abya Yala, today known as Mesoamerica, with origins in pre-Hispanic times. It is primarily based on collaboration, diversity, small-scale practices, regeneration, and the entanglement of various creatures, plants, and human communities. It represents sustainability by providing food and multiple annual harvests without degrading the soil's trophic network. Unlike plantation and exploitative monoculture systems, the milpa is characterized by openness and emergence. It operates as a small-scale, family-driven agricultural model that fosters networks. On a small plot of land, various crops grow together, creating space for multiple species by inventing forms of collaboration, cooperation, and mutual support, accommodating the available resources within a shared common space.

The paradigmatic example of collaboration within the milpa is seen in the "Three Sisters": beans, maize, and squash. Beans and maize establish a reciprocal support relationship that ensures their survival. The maize sprouts and grows first, providing a vertical structure for the beans, the younger sister, to find its way by wrapping around the corn sister, forming a double helix along its stem in a circumnutation process. The gift of the beans is enriching the soil by fixing nitrogen; this happens underground as a second layer of collaboration and reciprocity between Rhizobium bacteria and the beans. The former need to find refuge in an environment free of oxygen, beans will grow nodules attached to their roots able to host and provide Rhizobium bacteria with the necessary conditions. Squash, the youngest of the sisters will grow after, and the newcomer sister will help the older sister retain soil moisture. The "Three Sisters" grow together, sharing the soil as they share the light, leaving enough for others to thrive. "It is tempting that these three are deliberate in working together, and perhaps they are. But the beauty of the partnership is that each plant does what it does to increase its growth. But as it happens, when the individuals flourish, so does the whole".1The milpa is not limited to the three sisters; its openness accommodates other species, such as tomatoes, peppers, weeds, herbs, fruit trees, fungi, bacteria, insects, and animals, weaving a network of interdependencies where also the farmer is included. In the milpa, one thing connects with many others, forming a dynamic tapestry of relations, where one is with/on/for/by/from/toward another. The "Three Sisters" teaches us that each one comes with a potential or gift to offer others, and which also holds the potential to create forms of support and exchange with another. When one thrives, it helps the other, and in this way, they thrive better together.

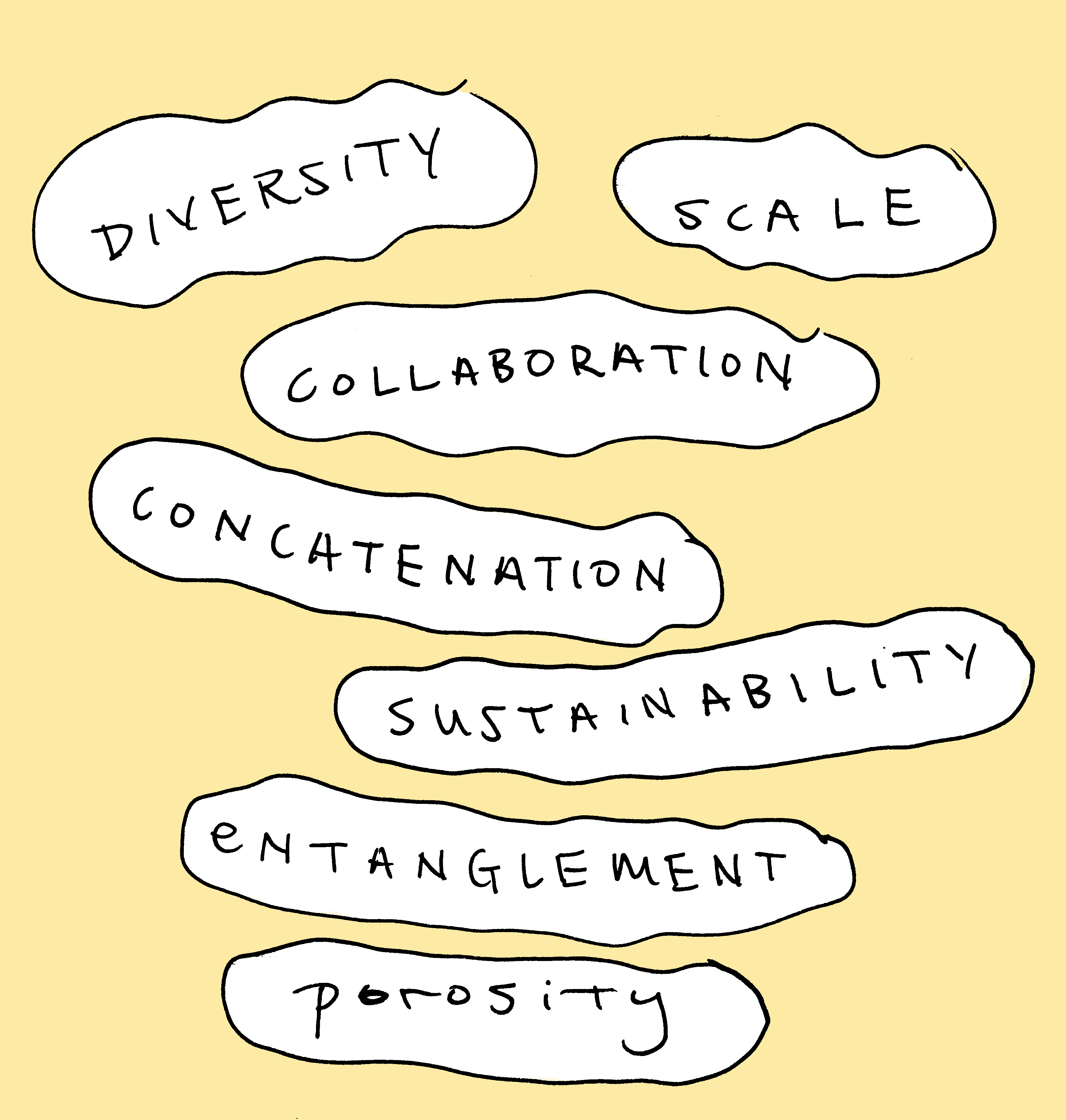

A vivid image of solidarity appears as the beans entwine and nearly embrace the maize—a moment of giving and receiving, of reciprocity, disappropiation2, porosity, vulnerability, and collaboration. Together, they find ways to survive and sustain each other. The milpa, as an ecosystem, represents a set of different positions and prepositional forms that create a decentralized network. The farmer is not necessarily a central figure but is instead part of a network of relations and interdependencies. The farmer is just another part of a tapestry of human and non-human interrelations, where one thing is never isolated, and never stands alone. The word milpa comes to us from Nahuatl, meaning crop on top of crops, allowing us to think about how different crops grow entangled and perhaps also how the milpa undergoes periods of decay and regeneration of the soil through composting. A set of driving principles characterize and enable the milpa to become a resilient and sustainable system. These principles include collaboration, diversity, regeneration, scale, and interdependence.

In this sense, the milpa stands as a counter-image to plantation and monoculture, both deeply rooted in the histories of capitalism and colonization. The plantation as a design enables a single species to thrive, it reflects and denotes homogeneity and transparency; an expression of a One-world worldview (Escobar, 2017) imposed as the sole valid and absolute Truth. Universalism, as a centrifugal and epistemological canon, creates separations, an abyssal gap (Sousa Santos, 2018) establishing itself as isolated, ubiquitous, and without exteriority. This rejects multiplicity, ambiguity, and opacity (Glissant, 1997), fostering an operational design that homogenizes everything. It not only threatens biodiversity but also leads to the destruction of ecosystems and the disappearance of possible worlds (Escobar, 2020). Achille Mbembe refers to these historical colonial processes, in conjunction with the technological and industrial sphere, as brutalism: "a contemporary process whereby power, as a geomorphic force, constitutes itself, expresses itself, reconfigures, acts, and reproduces through fractures, fissures, perforations, extraction, and depletion"3.

It is perhaps in the image of the milpa where we can find a counter-point based on collaboration and creating bridges between different epistemologies, disciplines, and ways of knowing, ecologies of knowledge (Sousa Santos, 2018). If we consider the milpa as a metaphor and a method applied to the design, could the act of enacting, imitating, or translating the milpa lead us to imagine and speculate on (more) collaborative and sustainable designs within the context of cultural and educational infrastructures? Both art and education play a crucial role in fostering imagination, inventing forms of community, and creating alternative epistemological landscapes.

The etymology of the word agriculture comes from the Latin root colere, which means to work, honor, care, and inhabit the land, giving rise to terms like cultivate, culture, and colonist. From a general perspective, it carries an instrumental character. As Vilém Flusser notes in "The Gesture of Planting"4, the central figure of the farmer uses and enjoys a plot of land that might otherwise be a forest or jungle. Planting implies domestication, anticipating and controlling a predictable outcome, unlike hunting or fishing, where results are far more uncertain. The milpa, as an agricultural technique, stands somewhere in the middle, holds a certain level of domestication between the "Three sisters" yet allows a diversity of species to develop multiple interrelations. The milpa belongs to a pre-industrial past. It reminds us of forms of relationship and survival. Where one can find its potential by offering it as a gift to others. Perhaps it allows us to start rethinking notions of use and ownership, encouraging networks of solidarity.

1 Kimmerer, Robin (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teaching of plants. Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, p.134.2 Mbembe, A. (2021, October). The Earthly Community. E-flux Architecture. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/coloniality-infrastructure/410015/the-earthly-community/

3 Mbembe, Achille (2022). The Earthly Community: reflections of the last utopia. Rotterdam: V2_Publishing, p.32.

4 Flusser, Villem (2014). Gestures. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 98

Mexican milpa. Photo by Iván Juárez